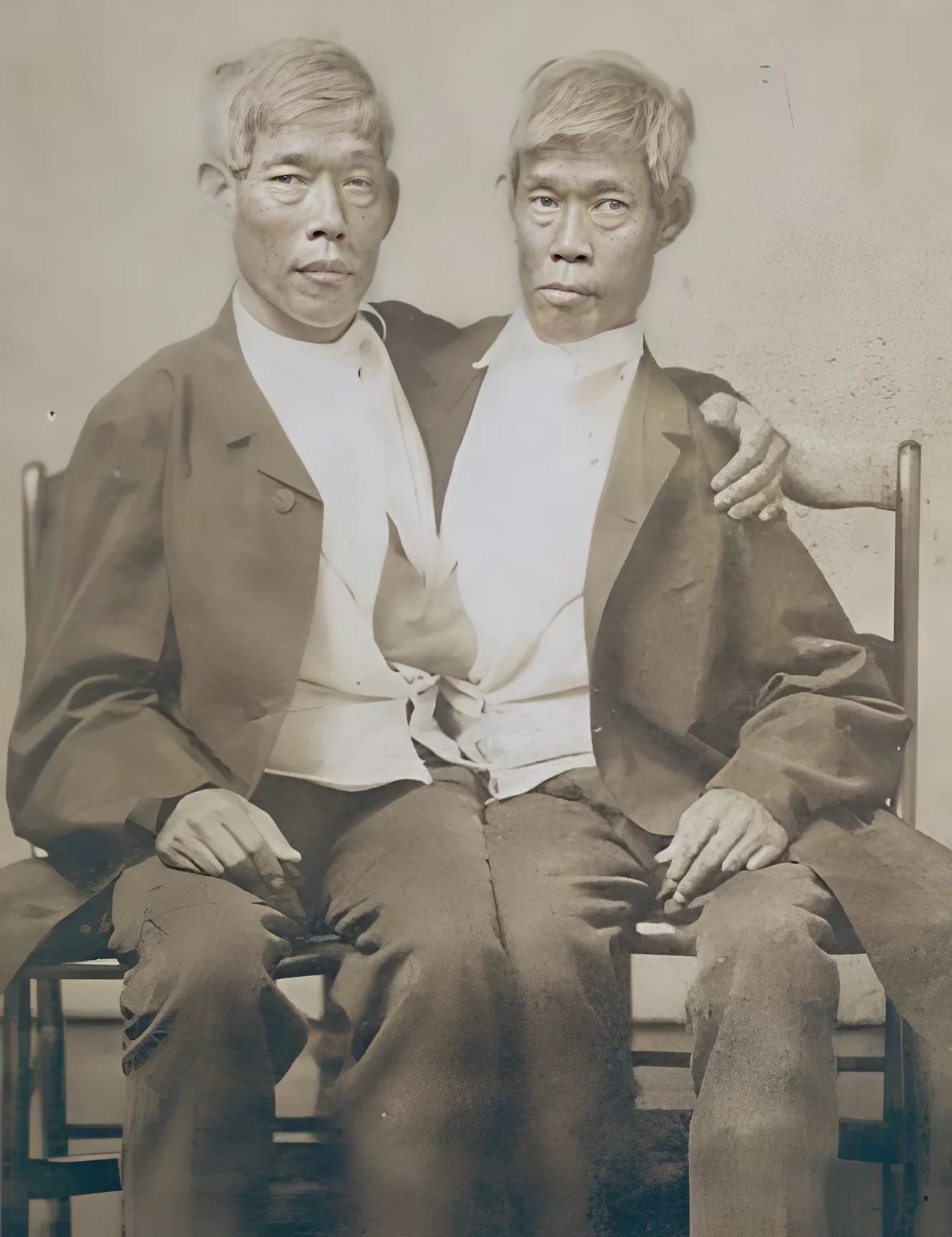

Chang and Eng Bunker were born in 1811 in a small fishing village in what was then known as Siam — today’s Thailand. From the moment they entered the world, their lives were marked by both awe and uncertainty. Joined at the chest by a 10-centimeter-wide band of flesh and muscle, the two boys also shared a liver, making them medically inseparable by the standards of the early 19th century.

At a time when conjoined twins were seen as medical anomalies or even omens, most assumed they wouldn’t live long. But Chang and Eng defied every expectation. Their physical bond became the least interesting thing about them. They grew strong, clever, and surprisingly independent in thought — even as they were physically inseparable.

By the time they reached their teens, their lives took a dramatic turn. Western traders and promoters saw potential in the brothers — not just as curiosities, but as performers. They began touring Asia, and eventually Europe, where crowds were fascinated not only by their appearance but by their personalities. They spoke several languages, told jokes, debated each other on stage, and carried themselves with grace and humor. They were never content to be mere spectacles; they demanded to be seen as individuals.

In England, their fame soared, and with it came the attention of a young woman named Sofia. She was drawn not to their uniqueness but to their kindness and intellect. Sofia dreamed of marrying them, of creating a life full of love and shared experiences. But 19th-century society was not ready for such a union. Her parents forbade the relationship, and the authorities refused to recognize or even consider the possibility of a legal marriage to conjoined twins. Heartbroken but undeterred, Chang and Eng moved on.

Eventually, their travels led them to America. Tired of life on the road, they settled down in the quiet countryside of North Carolina, where they reinvented themselves — not as entertainers, but as farmers. It was there that fate intervened once more.

In the nearby Yates family, Chang and Eng met two teenage sisters, Sarah and Adelaide. The girls were just 16, but over time, a deep affection grew between the couples. Despite the intense scrutiny of their neighbors and the disapproval of many in the conservative community, the love between them was undeniable.

In 1843, they held a double wedding — a ceremony that many expected would fade into scandal or failure. Instead, it marked the beginning of a remarkable family life. The sisters chose to live in separate homes, and the brothers followed a rhythm that became second nature: three days with Sarah, three days with Adelaide. It was unconventional, but it worked. They made it work — with love, patience, and a sense of humor.

Together, they had 21 children: ten fathered by Chang, eleven by Eng. The homes were lively, full of laughter, chores, and the noise of children playing. Against all odds, the Bunkers built a life that was rich, meaningful, and filled with love. Their children were healthy, their farms successful, and over time, even the harshest critics fell silent.

The end came as powerfully as the beginning. In January 1874, Chang fell ill with pneumonia. He died quietly in his sleep. A few hours later, Eng followed — not from illness, but, many believe, from heartbreak. It was as if one soul could not live without the other.

To this day, their descendants — spread across the United States — speak with pride about their remarkable ancestors. And the world remembers them, too. The term “Siamese twins” was coined in their honor, but what they left behind goes far beyond medical terminology. Chang and Eng proved that even the most extraordinary life can be filled with love, purpose, and a quiet kind of heroism.